どうして金融緩和は失敗するか

金利に関するオーストリア学派の考え方ですね。トレンドに関する記事ですがタイミングに関するものではありません。

一般企業なら、赤字が続くと倒産します。

政府が赤字なら、いくらでも借金できる?そんな訳はない、それが社会主義がうまくいかない理由。ただしいつ破局を迎えるか、それを正確に予想するのは難しい。

ソ連の例をみると建国1922年から1991年崩壊まで実に70年を擁しています。ニクソンが金交換停止したのが1971年でこれ以降政府債務の膨張が始まっています。まだ50年位しか立っていません。

記事が長すぎて、訳はいつも以上にヤッツケです。わかりにくところがあれば指摘を。

Authored by Alasdair Macleod via GoldMoney.com,

The major economies have slowed suddenly in the last two or three months, prompting a change of tack in the monetary policies of central banks. The same old tired, failing inflationist responses are being lined up, despite the evidence that monetary easing has never stopped a credit crisis developing. This article demonstrates why monetary policy is doomed by citing three reasons. There is the empirical evidence of money and credit continuing to grow regardless of interest rate changes, the evidence of Gibson’s paradox, and widespread ignorance in macroeconomic circles of the role of time preference.

ここ2,3か月で経済状況が急減速した、これが中央銀行の金融政策を変えさせた。よく知られた通貨膨張主義社の失敗が待ち構えている、金融緩和で金融危機を決して止めることはできないことが解っているにもかかわらずだ。この記事で指し示すのは、どうして金融政策が万事休すかということを3つの理由で解説する。金利変化によらず、マネーと与信は増え続けるという経験則が厳然としてある、Gibsonのパラドックスの証拠(金利と物価水準には正相関がある。Gibson以前には通貨量を増やすと金利が下がり物価が上がると考えられていた。)、そして time preference (現在価値と将来価値の違い)に関するマクロ経済を皆が無視しているという3点だ。

The Fed’s rowing back on monetary tightening has rescued the world

economy from the next credit crisis, or at least that’s the bullish

message being churned out by brokers’ analysts and the media hacks that

feed off them. It brings to mind Dr Johnson’s cynical observation about

an acquaintance’s second marriage being the triumph of hope over

experience.

FEDが金融引き締めから後退したことで世界経済を次の与信危機から救った、少なくとも証券会社のブローカーやメディアの記者は強気メッセージでこれを褒めそやす。この状況はDr. Johnsonの、友人の再婚に関する彼の皮肉な格言を思い起こさせる、「経験よりも期待が優る」というものだ。

The inflationists insist that more inflation is the cure for all

economic ills. In this case, mounting concerns over the ending of the

growth phase of the credit cycle is the recurring ill being addressed,

so repetitive an event that instead of Dr Johnson’s aphorism, it calls

for one that encompasses the madness of central bankers repeating the

same policies every credit crisis. But if you are given just one tool to

solve a nation’s economic problems, in this case the authority to

regulate the nation’s money, you probably end up believing in its

efficacy to the exclusion of all else.

通貨膨張主義者はこう主張する、インフレがすべての経済問題を解決する。今回の場合、与信サイクル拡大の終盤での積み上がる懸念は循環性の病状であり、Dr. Johnsonの格言を出すまでもなく繰り返されるものだ、これが思い起こさせるのは、どの与信サイクルでも中央銀行は常軌を逸して同じ政策を繰り返すということだ。しかし皆さんは国家的経済問題の解法を一つだけ示されたとすると、これは今の状況で言うと当局が通貨を監督管理しているということだが、皆さんはたぶん他のどのような手法よりもその政策の有効性を最終的に信じることになろう。

That is the position in which Jay Powell, the Fed’s chairman finds himself. Quite reasonably, he took the view that the Fed’s marriage with the markets was bound to go through another rough patch, and the Fed should use the good times to prepare itself. Unfortunately, the rough patch materialised before he could organise the Fed’s balance sheet for its next launch of monetary bazookas.

The whole monetary planning process has had to go on hold, and a mini-salvation of the economy engineered. To be fair, this time it is Washington’s tariff fight with China and its alienation of the EU through trade protectionism that has interrupted the Fed’s plans rather than the Fed’s mistakes alone. But by taking early action the hope is the Fed can keep confidence bubbling along for another year or two. It might work, but it will need a far more constructive approach towards global trade from America’s political-security complex to have a sporting chance of succeeding.

それはJay Powellの立場だ、FED議長自らがその立場を明らかにすることだ。これは全く合理的だ、彼はFEDの市場との結婚の将来を見通し、難しい問題に直面している、そしてFEDはそれに備える時だ。残念なことに、彼がFED議長として次に金融バズーカとしてFEDバランスシートを整える前に問題が顕在化した。金融計画全体が保留となり、小規模な経済救済と成らざるを得なかった。公平に見て、今回はFEDの誤政策というわけではなく、ワシントン政府が中国と関税戦争を始め、欧州と保護貿易で対立した、これがFEDの計画を中断させた。しかし対応が素早かったために、FEDはまだ今後数年はバブルを維持してくれるだろうという期待が残った。これがうまくゆくかもしれない、しかし米国の安全保障を考える上で、世界貿易政策としてはもっと建設的なものが必要だろう。

However, buying off a crisis by more money-printing does not represent a solution. It is commonly agreed that the problem screaming at us is too much debt. Yet, the inflationists fail to connect growing debt with monetary expansion. The Fed’s objective is to encourage the commercial banks to keep expanding credit. What else is this other than creating more debt?

しかしながら、危機を回避するために、さらに紙幣印刷をするというのは解決策ではない。だれもが認めることだが、あまりに大きな債務を抱えている。ただ、通貨膨張論者は債務増加と金融緩和を関連付けない。FEDの目的は商業銀行の貸出拡大だ。いったいこれ以上に債務を増やす方法があるだろうか?

Powell is surely aware of this and must feel trapped. However, what his feelings are is immaterial; his contractual obligation is to keep the show on the road, targeting self-serving definitions of employment and price inflation. He will be keeping his fingers crossed that some miracle will turn up.

Powellはたしかにこのことに気づいており罠に落ちいているに違いない。しかしながら、彼がどう感じるかはどうでも良い:彼の責務は以下のことを実行することだ、自ら定めた雇用と物価目標を守ることだ。彼はなにか奇跡でも起きないかと願っているに違いない。

It is too early to forecast whether the Fed will manage to defer for

just a little longer the certainty that the monetary imbalances in the

economy will implode into a singularity, whereby debtors and creditors

resolve their differences into a big fat zero. That is not the purpose

of this article, which is to point out why the underlying assumption,

that interest rates are the cost of money which can be managed with

beneficial results, is plainly wrong. If demand for money and credit can

be regulated by interest rates, then there should be a precisely

negative correlation between official interest rates and the quantity of

money and credit outstanding. It is clear from the following chart that

this is not the case.

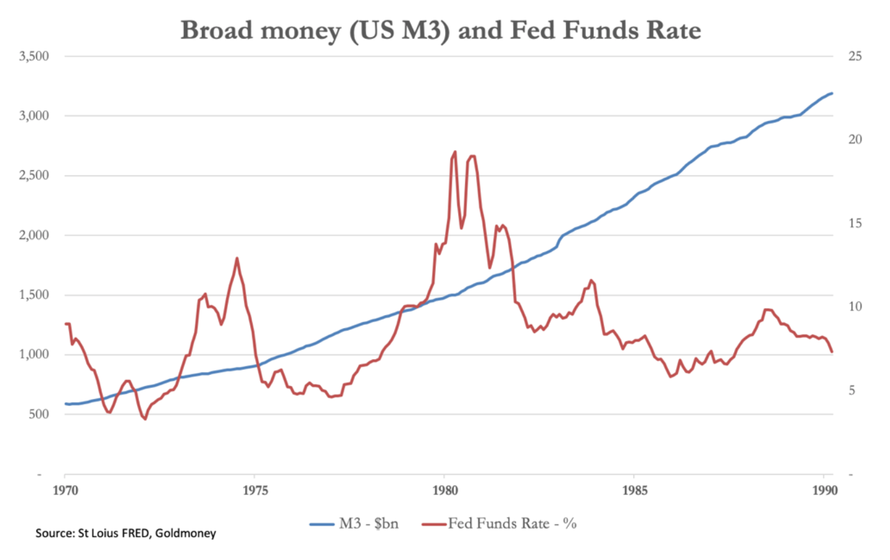

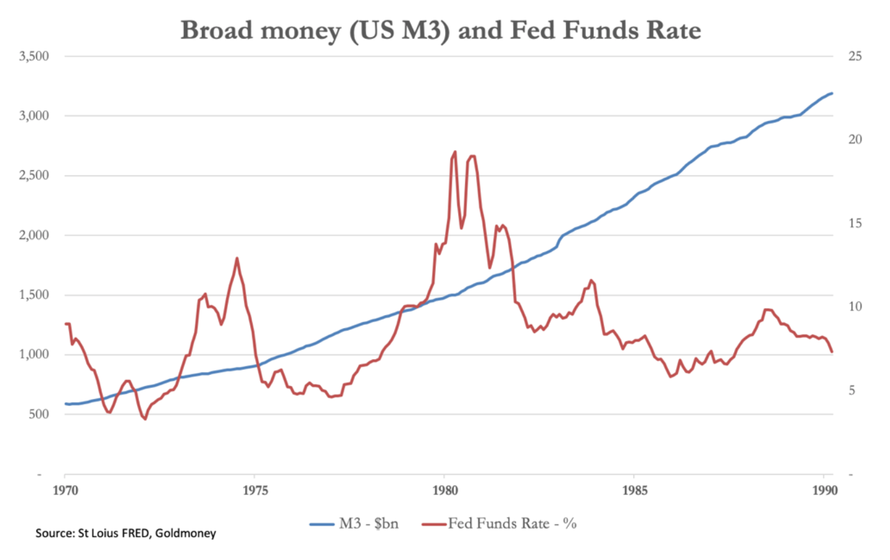

FEDが金融不均衡の崩壊を後伸ばしする動きにでるかどうか判断するのにはまだ早すぎる、この崩壊点を迎えると貸しても借りてもチャラになる。この記事の目的はそういうことを解説するものではない、その議論の背景にある仮定がまったく間違っているかを指摘することだ、金利とはお金のコストであり、これが有益な結果を生み出すように管理されるべきだ、しかしこれが全くそうなっていない。もし資金需要や債務が金利で管理されるなら、公式金利と、貨幣量や与信総量、との間には負の相関が在るはずだ。下のチャートを見れば明らかだがこの関係が成り立っていない。

This chart covers the most violent moves in Fed-directed interest rates ever, following the 1970s price inflation crisis. Despite the Fed increasing the FFR from 4.6% in January 1977 to 19.3% in April 1980, M3 (broad money and bank credit) continued to increase with little variation in its pace. Falls in the FFR designed to stimulate the economy and prevent recession were equally ineffective as M3 continued on its straight-line path after 1980 without significant variation, and it is still doing so today. There is no correlation between changes in interest rates, the quantity of money, and therefore the inflationary consequences.

このチャートが示すのは、FEDが管理する金利が最も大きく動いた時期のものだ、1970年代の物価インフレ危機の後を示す。FEDはFFRを1977年1月の4.6%から1980年4月の19.3%まで増やしたが、M3(広義マネーと銀行貸出)は増加を続けた、その増加速度にはほとんど変化がなかった。景気刺激と景気後退回避でFFRを下げたが効果はなかった、M3は1980年以降も大きね変化はなく増加を続けた、そして現在も増え続けている。これを見て解るように金利変化と貨幣量の間に相関は無い、そしてインフレが起きている。

From the chart above, it is clear that the central tenet of monetary

policy, that the quantity of money can be regulated by managing interest

rates, is not borne out by the results, and therefore the role of

interest rates is not to regulate demand for credit as commonly

supposed. This is confirmed by Gibson’s paradox, which demonstrated that

a long-run positive correlation existed between wholesale borrowing

rates and wholesale prices, the exact opposite of that assumed by modern

economists. This is shown in our second chart, covering over two

centuries of British statistics.

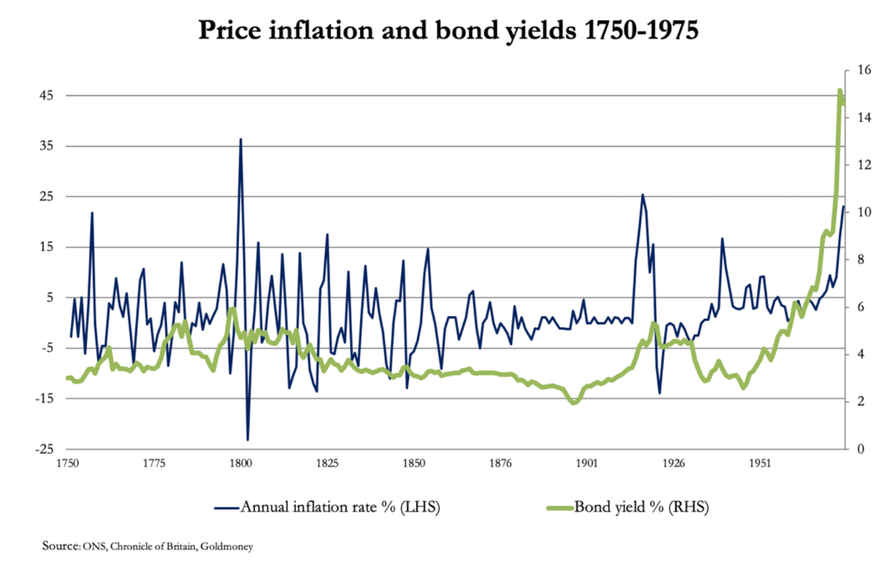

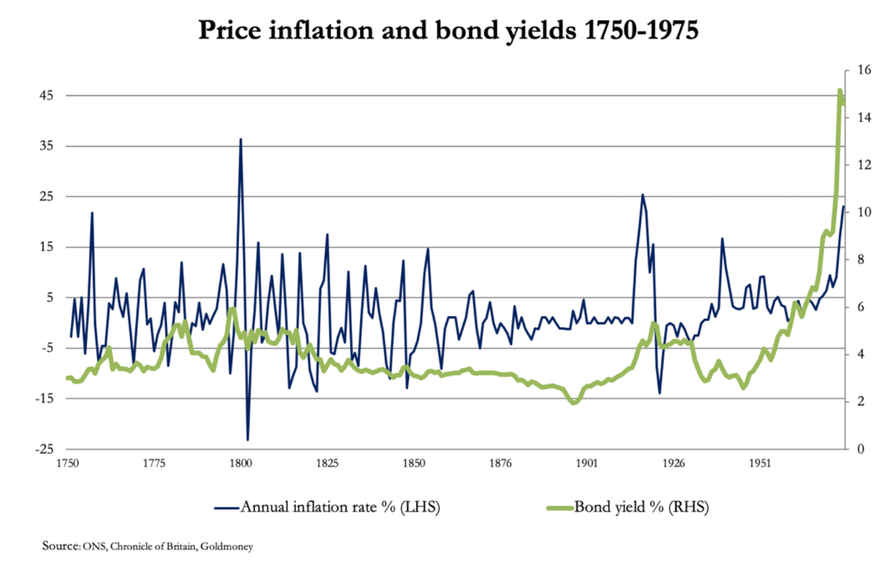

上のチャートで示すように、金融政策の主要課題は明らかだ、「金利で通過量を制御できる、」なんてことは受け入れることができないのは結果を見れば明らかだ、そして一般に思われているように「金利の役割は、一般に信じられているように与信需要を調整できる」なんてわけでもない。これはGibsonの逆説で確認されている、長期的には借金金利と卸売物価の間には正の相関があるが、近代経済を見るとこれとは全く逆の事が起きている。この状況を示すのが第二のチャートだ、2世紀に渡る英国の統計を示している。

Economists dismissed the contradiction of Gibson’s paradox because it conflicted with their set view, that interest rates regulate demand for money and therefore prices[i]. Instead, it is ignored, but the evidence is clear. Historically, interest rates have tracked the general price level, not the annual inflation rate. As a means of managing monetary policy, interest rates and therefore borrowing costs are ineffective, as confirmed in our third chart below.

エコノミストはギブソンのパラドックスの矛盾を無視する、その理由は既存概念からすると混乱するからだ、というのも「金利は資金需要を調整しその結果物価も調整する」と多くの人は理解している。無視されるにもかかわらず、証拠は明らかだ。歴史的にみると、金利は物価レベルを追いかける、インフレ率ではない。金融政策の一環として、金利や借金コストは無効だ、これは3枚目のチャートを見れば解ることだ。

The only apparent correlation between borrowing costs and price inflation occurred in the 1970s, when price inflation took off, and bond and money markets woke up to the collapsing purchasing power of the currency.

資金調達コスト(金利)とインフレ率のあいだに明らかな相関があったのは1970年代だけだ、この時物価インフレ率が上昇し始めた、そして債権と短期金利市場が目覚めて通貨の購買力が崩壊した。

The explanation for Gibson’s paradox, which embarrassingly eluded all the great economists who tackled it, is simple. It stands to reason that if the general price level changes, in aggregate businessmen in their calculations will take that into account when it comes to assessing the level of interest they are prepared to pay and still make a profit. If a businessman expects higher prices in the market, he will expect a higher rate of return and therefore be prepared to pay a higher rate of interest. And if prices are lower, he can only afford to pay a correspondingly lower rate. This holds true when capital in the form of savings is limited by the preparedness of people to save, and businesses have to compete for it.

ギブソンのパラドックスの解説、多くの著名なエコノミストが挑戦したがみなこれに言及することを避けた、この解説はとてもシンプルなものだ。こういうビジネスマンの行動は理にかなうものだ、もし物価がレベルが変わったら、利に聡いビジネスマンたちは金利が高くても利益を出せると推測するだろう。もしビジネスマンが市場での物価上昇を予想するなら、儲けも増えると期待し金利が高くても納得するだろう。もし物価が下がると、彼らは低金利しか許さないだろう。貯蓄をしようとする人の資金に限定するならこれも正しいことだ、そしてビジネスもこれとの競合せざるを得ない。

Today, Gibson’s paradox does not appear to apply, partly because capital is no longer scarce (thanks due to central banks) and partly because the abandonment of the Bretton Woods agreement has led to indices of the general price level rising continually. To these factors must now be added wilful misrepresentation of price inflation in official statistics, a deceit that will almost certainly end up destabilising attempts at economic management even further when discovered.

現在ではギブソンのパラドックスは適用されるわけではない、その一因は資金は潤沢にある(これは中央銀行のおかげだ)そしてもう一因はBretton Woods合意の放棄で物価は常に上昇し続けているためだ。これらの要因に加えて、今では公式統計の物価インフレ率は故意に捻じ曲げられている、このデタラメが経済運営を不安定にしている。

These points notwithstanding, the belief that interest rates are a price which regulates demand for money is disproved. The mistake is to ignore the human dimension of time preference and assume there is no reason for a difference in intertemporal values, the value of something today compared with later. To understand why the degradation of value over time becomes a necessary element of compensation in lending contracts, we must examine in more detail what interest rates actually represent. Only then can we fully understand why they do not correlate with changes in the general level of prices and the growth of credit, which makes up the bulk of M3 in the first chart.

こういう指摘にもかかわらず、金利が資金需要を調整するという間違った考えが信じられている。この誤解は人が time preference (現在価値と将来価値の違い)を無視していることから生まれる、そして時間に伴う価値の変化はないと仮定してしまっている、現在の価値と将来の価値とを較べる時だ。時間と共に価値はどうして劣化するかを理解すれば、貸付契約の対価が必要となることがわかる、これからもっと詳細に金利とは何かについてもっと知らなければならない。これを知ることで、我々は価格レベルの変化と与信増加の間にどうして相関が無いかを良く理解できるようになる、この与信が最初のチャートのM3で示したものだ。

In all lending agreements, interest represents a number of factors.

There is an element representing a risk premium, depending on the credit

standing of the borrower, the entrepreneurial risk, and the purpose for

which the loan is made. There is also a generally agreed underlying

rate which in a market economy reflects pure time preference, referred

to by Austrian economists as the originary rate. Time preference is the

difference in the value placed on an action intended to satisfy sooner

compared with the value placed on the same satisfaction achieved at a

later date.

どのような貸借契約においても、利息はいろいろな要因を反映している。リスク・プレミアム要因としては、借り手の信用、起業家リスク、そして貸出目的がある。その時々の誰もが認める金利がある、経済環境に応じたtime preference 時間先取りの金利によるものだ、これをオーストリア経済学派は originary rate という。Time preference 時間先取りというのは同じ満足度が得られるにしても、早く実現できるものと後ほど得られるものでは価値に違いがあるということだ。

Mainstream macroeconomists deny the existence of time preference, claiming that interest represents the rental of money. If that is all interest represents, then it can be reduced for the benefit of producers and consumers, and beyond savers losing out, no other consequences need occur. Furthermore, the denial of a subjective human element is always necessary for a mathematical approach to prices to be credible.

主流派マクロ経済学者はこの time preference 時間先取りの概念を否定する、そうではなく金利とはお金の貸出料金だという。これが金利の全てというなら、producers(貸し手)とconsumers(借り手)ともに恩恵は少なくなる、ましてや貯蓄は意味をなくする、他の意味合いが必要だ。更にいうと、人の存在を否定してしまうと、価格の裏付けは数学的な手法に頼ってしまう。

Despite it being unfashionable, we must briefly summarise pure time preference theory. Time preference is always present because time for any economic actor is finite and therefore has value. The more immediately that an action results in a satisfaction the more valuable that satisfaction compared with an action which leads to the satisfaction being delayed. It has been referred to by the old adage that a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.

それほど派手ではないが、我々は簡単に、純粋なtime preference theory を理解せねばならない。Time preferenceというのは常に存在する、というのもどの経済主体にとっても時間は有限で価値のあるものだからだ。もっと卑近に説明すると、同じ満足の得られる行為でも後からよりもいまえられた方がより価値がある。このことは昔からの格言でよく言われることだ、ヤブの中の二羽より手中の一羽。

The key to understanding the importance of time preference is to realise it is a human characteristic, and not something that emanates from the properties of individual goods and services. Intertemporal price differences can vary considerably between products, mainly due to their individual supply and demand characteristics. Because pure time preference is an underlying determinant of human action, the general rule is that the greater the difference in time between deciding on a course of action and the delivery of the satisfaction, the less the present value of that future action. From our individual experiences, we all know this to be true.

time preferenceの重要性を理解する鍵は人間の特質に気づくことだ、それは個々のモノやサービスから発せられるものではない。一時的な価格の変動は製品によってかなり変わる、主には需給関係に依存してだ。純粋な time preferenceは人間の行動が基準となるために、基本的なルールとして主に行動を起こす決断をした時と満足を得るときに大きな違いがある、将来の行動に対する現在価値は小さなものだ。我々の個人的な経験から、だれでもこのことをよく知っている。

Time preference is therefore the general intertemporal value placed on goods and services by consumers. It is not under the control of the producer, or for that matter a central bank. It is the consumer, the end-buyer of everything, that confirms the level of discount on future values, because consumers are humans acting with their human preferences.

Time preferenceとは消費者にとってもモノやサービスの一時的な価値とみなされる。生産者が制御する価値ではない、ましてや中央銀行でもない。それは消費者、最終的買い手となる、将来には価値が差し引かれる、というのも消費者は人間であり、人の好みに基づいて行動する。

In order to obtain monetary capital for any reason, the owners have to be persuaded to temporarily part with it for a compensation related to their general time preference. This is because they are being asked to defer their consumption, which is represented by the money borrowed. For convenience and by convention, compensation for the loss of the availability of money for immediate spending is expressed as an annualised interest rate. In this way, the variations of time preference for the full range of opinions and judgements of consumers over the whole gamut of goods and services finds expression in a basic, or originary rate of interest on money.

何らかの理由で金融資産を持とうとすると、その所有者は一時的な圧力を受ける、一般的な time preference に関する埋め合わせだ。だからこそ借金による消費は先延ばしできないかと自問する。伝統的に、直ちに支出するお金がない場合に、その埋め合わせを金利で表現する。こういうふうにして、全てのモノやサービスに対して消費者は異なるtime preference を持つ、これがお金に対する金利の始まりだ。

This fundamental human ranking of values matters to businessmen, because the longer it takes to produce a consumer good, the less the distant value of that good can be expected to be, expressed in today’s money. In assembling their capital resources, they take this time-related expense into account.

Therefore, in order to reduce the loss in value due to time preference, businessmen will always prefer the most efficient route available to final production. If, as is always the case today, a central bank commands through interest rate policy that the discount on future values is reduced, businessmen are no longer disciplined to prefer the most efficient route to production. The intertemporal discount is still there, but the suppression of originary interest rates by a central bank imposing a lower rate on the market creates an opportunity unrelated to the singular objective of providing consumer satisfaction.

この人間に備わる価値のランク付けがビジネスマンにとっては大切だ、というのも消費物を生産するのに時間がかかるほどに、そのものの予想価値が現在価値から乖離する。資金調達するときに、彼らはこの time preference による損失を考慮する。ビジネスマンは常に最終製品を最も効率的に生み出す方策を望むだろう。現代ではありふれたことだが、もし中央銀行が金利英作で将来価値を下げるなら、ビジネスマンはもはや規律をもって効率的な生産をしなくなる。時間に関する割引がそこにはある、しかし中央銀行が低金利で本来の金利を抑圧するなら、消費者の満足とは無関係な好機を生み出す。

This is why suppressing interest rates leads to malinvestments, exposed when interest rates subsequently rise. This is what the current hiatus in the stalling US economy is really about.

これがどうして金利抑圧が malinvstments 不当な投資(訳注:たとえばテスラとかソフトバンク、太陽光発電のようなビジネス)を引き起こすかという理由だ、その後金利が上昇するとこれが明白になる。これが米国経済が現在の停滞に陥っている理由だ。

It is clear, irrespective of monetary policy, that the originary interest rate is set by individuals in their roles as economic actors. That is not to say that in their decisions they are uninfluenced by official interest rates, but there is a tight limit to that influence. Instead, individuals will seize the opportunities presented by the difference between their own originary rate of interest and that set by the monetary authorities. An obvious example is residential property, where supressed interest rates persuade individuals to borrow cheap mortgage money to buy houses, purely because the interest payable is less than that suggested by personal time preferences. The same is true of financing the purchases of purely financial assets, and it is also a key reason behind the expansion of consumer credit.

金融政策とは無関係に、源金利は経済要因により個別に定められることは明らかだ。だからといってビジネスマンが公式金利の影響を受けないわけではない、そうではなく影響には限界がある。むしろ、自らの源金利と金融政策によって定めらた金利の違いによって、個々人は機会を捉えるだろう。明らかな例は住宅不動産だ、この分野では住宅購入のための借金を促進するために金利が抑えられている、なぜならば純粋に支払い可能な金利が個人的な time preference より小さくなるようにしている。同様のことが金融資産購入の際の融資にも当てはまる、そしてこれはまた消費者金融が拡大する重要な原因だ。

The suppression of interest rates to levels below those collectively determined by consumers in their time preferences is the fundamental source of inflations, booms, bubbles, and subsequent busts.

消費者が自然に持つ time preference よりも低い金利に抑え込むことで、インフレ、ブーム、バブルその後のバブル破壊を引き起こす基礎を形成する。

Essentially, a central bank’s interest rate policies distort markets, but they cannot significantly change that originary rate of interest. That is in the lap of time preference, set semi-consciously by consumers. The relationships between lenders and borrowers of monetary capital are further distorted by tax, because today’s governments commonly regard interest income as quasi-usurious and therefore a target for reducing the implied inequality of some individuals possessing significant levels of savings compared with others.

基本的なことは、中央銀行の金利政策は市場を歪める、しかし彼らも本来の金利を大きく変えることはできない。本来の金利というのは time preference から生じるものであり、消費者の判断によるものだ。金融資本に関して貸し手と借りての関係は税金で大きく歪んでいる、というのも今日の政府の立場は金利というのは高いもので、貯蓄の多い人とそうでない人の格差を緩和するために利息は課税対象となる。

Taxation on interest interferes with time preference, which was demonstrated through its absence on savings in the two most successful post-war economies, those of Japan and Germany. In Japan, tax-free post office savings accounts grew as a means of earning interest without being taxed, and in Germany the Federal Central Tax Office didn’t much bother collecting the withholding tax on bond interest at least until the 1980s, because to do so simply chased money out of Germany into savings accounts in Luxembourg and Switzerland beyond the reach of the tax office. Consumers in both Japan and Germany still retain a general savings habit that contributes to a relatively stable level of time preference, characteristics which have been central to their economic success.

利息に課税するとこで time preference に介入し、第二次世界大戦後の最も成功した2経済圏において貯蓄において time preferenceが無くなってしまった、日本とドイツだ。日本においては、郵便貯金の利息を非課税にしたので、この口座が増えた、そしてドイツではFederal Central Tax Officeは1980年台まで国債金利に課税しなかった、このために預金口座がドイツからルクセンブルグやスイスに逃げ出した、税金回避のためだ。日独共に消費者の貯蓄習慣は保たれ安定した time preferenceを保った、これが経済的成功の源となった。

The examples of Germany and Japan contrast with other socialised economies where savings have been discouraged through tax discrimination. The replacement of savings in the US and UK by bank credit and central bank base money has been a sad failure in comparison.

日独の例は社会主義経済とは際立つものだ、社会主義国では税金のために貯蓄の意欲が削がれた。米国や英国では銀行からの借金が貯蓄の代替となり、中央銀行のベースマネーが悲しい結末を迎えた。

So far, we have only addressed time preference on the assumption there is no change in money’s purchasing power. If, as is always true today, money’s purchasing power is continually declining, then to the extent the general public is aware of it, that widens the gulf between official interest rates and time preference even further. And if savers realise the true extent that the currency of their savings is losing purchasing power instead of believing self-serving government statistics, they could be forgiven for discounting future satisfactions even more heavily.

今までのところ、time preferenceに関してマネーの購買力に変化はないと仮定してきた。現在ではあたりまえのことだが、もしマネーの購買力が下落を続けるなら、一般大衆もこのことに気づく、こうなると公式な金利と time preference の間の溝が広がる一方だ。そしてもし預金者たちが、自ら貯蓄した通貨が政府統計と違い購買力を失っていることに気づくと、将来の満足が大きく割引されているのも無理はない。

This explains why, when the authorities respond to rising price inflation by raising interest rates, all they are doing is belatedly attempting to narrow an already widening gap between their version of where interest rates should be and the market’s rising originary rate. The expansion of bank credit does not slow, because the gap is still there and increasing as well.

この状況が、どうして、どういうときに当局が金利引き上げで物価上昇に対処するかを説明してくれる、彼らはギャップを狭めようとしている、本来の金利がどこにあるべきか、ということと市場が本来の金利を押し上げていることとのギャップだ。銀行与信の拡大は鈍化することはない、というのもこのギャップはまだ存在し広がり続けているからだ。

We saw this demonstrated in the 1970s, when rising interest rates failed to slow demand for credit, which continued to rise regardless. The rate of price inflation was also rising, persuading borrowers that the purchasing power of money was falling at an accelerating rate, thereby increasing their time preferences faster than compensated for by official interest rates.

我々はこの状況を1970年代にも目の当たりにした、金利上昇局面で与信需要は鈍化しなかった、なにがあろうと与信需要は増え続けた。同時に物価上昇も進行した、借り手を説得するのはこういう論法だ、金利上昇が加速するほどにマネーの購買力は下落する、しかるに、本来状況を補償するはずの公式金利よりも time preference増加の方が早い、という論法だ。

That ended in the early 1980s, when expectations of escalating prices were finally broken by 20%+ prime rates. In the 1980s demand for credit continued to increase, despite falling interest rates, because of financial and banking liberalisation which more than offset the failures associated with malinvestments. Broad money continued to grow with minimal variation as if nothing had happened, as it still does today.

これが終了したのは1980年代はじめのことだ、プライムレートが20%を超えて物価上昇が収まった。1980年代になると与信需要は引き続き増加した、金利下落にもかかわらずだ、というのも金融銀行自由化が進みmalinvestmentによる破綻を相殺したのだ。Broad moneyは躊躇なく増加を続けた、まるで何事もなかったように、これが現在も続いている。

The European Central Bank should pay attention to its failures as well. Its introduction of negative deposit rates, in defiance of all-time preference, has failed to stimulate production and consumption beyond government spending. Admittedly, negative rates have not generally been passed on to businesses and borrowing consumers, often for structural reasons. Instead, the ECB’s negative interest rates have benefited profligate Eurozone governments, allowing them to tax savers deposits instead of paying for time preference. It should be clear that negative interest rates cannot be justified so long as humanity values a satisfaction today more than the same satisfaction at a future date.

ECBでの失敗も注目すべきだ。彼らはマイナス金利を導入した、前代未聞の挑戦にもかかわらず、生産や消費を刺激することができなかった、政府歳出が増えただけだ。たしかに、マイナス金利はビジネスや個人債務には適用されなかった、多くは構造的な理由からだ。しかしながら、ECBのマイナス金利は放蕩を続ける欧州政府にとっては恩恵のあるものだった、そういう国では預金に課税することを可能にし、 time preference を免れた。ここで明らかにすべきだが、マイナス金利は人間の価値観から正当化されるものではない、何らかの行為で現在得られる満足が将来の満足よりも価値があると感じる人間の感性だ。

While the evidence is that interest rate policies fail to regulate

the pace of monetary inflation, the seeds of economic crisis were sown

by earlier interest rate suppression. Because suppression of interest

rates below the originary rate set by the public’s time preference

always leads to malinvestments, subsequent increases in interest rates

always lead to those malinvestments being exposed. The response by

businesses is always the same: mothball or dispense with the

malinvestments.

金融政策が金融インフレを生み出すことに失敗した一方で、金利抑制により経済危機の種がまかれた。多くの人の持つ time preferenceにより生み出される本源的金利よりも実金利を抑制することはいつもmalinvestments(すぐに思い当たるのが、テスラやソフトバンク、太陽光発電等)を引き起こし、その後の金利上昇局面では常にこれらの malinvestmentは無防備になる。ビジネス面での対応はいつも同じことだ:malinvestments は先送りになるか取りやめとなるかだ。

Banks sense the mood-change in their customers and the associated increase in lending risk. They restrict their credit lines and working capital facilities to those they deem vulnerable, usually the medium and smaller enterprises that make up Pareto’s 80% of the economy[ii]. The economy then runs into a brick wall with a rapidity that surprises everyone. Labour shortages disappear, followed by employees being laid off. An unstoppable process of correcting earlier malinvestments gathers pace.

銀行は顧客の mood-change やそれに伴う貸出リスク増加を感じ取る。彼らは与信限度を引き締め、脆弱とみなされる企業への投資資金の適正化を計る、一般的には中小企業に対するもので、パレートの法則で経済の80%を占める部分だ。経済は急速に手詰まりになり誰もを驚かす。労働力不足は消え去り、労働者は解雇される。初期の malinvestment はとどまるところを知らず調整される。

This is the point in the credit cycle at which we appear to have arrived today. If only central bankers had taken the long-run evidence of their own statistics seriously, if they had only paid attention to the message from Gibson’s paradox, and if they had noted the madness of doing the same thing time after time despite it not working, we would have been blessed with a far greater degree of economic stability, instead of the increasing certainty of another financial and systemic crisis.

ここで述べたことが現在我々が到達している与信サイクルだ。もし中央銀行が自らの長年の行動とその結末を真剣に評価する場合に限り、そして彼らがギブソンのパラドックスの意味するところに注意を払うならば、さらには彼らが何度も何度も約にも絶たない同じことをしてきたことに気づくなら、我々は経済安定が高まる福音を受けることだろう、むしろ今は次の金融システム危機が来ることがどんどん確からしくなっている。

As for the hope that cutting interest rates will somehow lead to an expansion of bank credit, don’t hold your breath. The other lesson we should all learn is money supply continues to increase, if not in the form of bank credit then in the form of central bank base money. This is because the alternative of widespread bankruptcies is always unpalatable to a socialising state.

金利を切り下げることでなんとかして銀行与信拡大を望むが、あまり期待しないことだ。他の教訓としてはマネーサプライは増加を続けていることを学ぶことだ、銀行の与信供与ではなく、中央銀行のベースマネーの形で増えている。だからこそ、よく知られた破綻以外に、社会主義国ではいつも受け入れがたい(社会主義はやがて破綻する)。

The major economies have slowed suddenly in the last two or three months, prompting a change of tack in the monetary policies of central banks. The same old tired, failing inflationist responses are being lined up, despite the evidence that monetary easing has never stopped a credit crisis developing. This article demonstrates why monetary policy is doomed by citing three reasons. There is the empirical evidence of money and credit continuing to grow regardless of interest rate changes, the evidence of Gibson’s paradox, and widespread ignorance in macroeconomic circles of the role of time preference.

ここ2,3か月で経済状況が急減速した、これが中央銀行の金融政策を変えさせた。よく知られた通貨膨張主義社の失敗が待ち構えている、金融緩和で金融危機を決して止めることはできないことが解っているにもかかわらずだ。この記事で指し示すのは、どうして金融政策が万事休すかということを3つの理由で解説する。金利変化によらず、マネーと与信は増え続けるという経験則が厳然としてある、Gibsonのパラドックスの証拠(金利と物価水準には正相関がある。Gibson以前には通貨量を増やすと金利が下がり物価が上がると考えられていた。)、そして time preference (現在価値と将来価値の違い)に関するマクロ経済を皆が無視しているという3点だ。

The current state of play

現状を見ると

FEDが金融引き締めから後退したことで世界経済を次の与信危機から救った、少なくとも証券会社のブローカーやメディアの記者は強気メッセージでこれを褒めそやす。この状況はDr. Johnsonの、友人の再婚に関する彼の皮肉な格言を思い起こさせる、「経験よりも期待が優る」というものだ。

通貨膨張主義者はこう主張する、インフレがすべての経済問題を解決する。今回の場合、与信サイクル拡大の終盤での積み上がる懸念は循環性の病状であり、Dr. Johnsonの格言を出すまでもなく繰り返されるものだ、これが思い起こさせるのは、どの与信サイクルでも中央銀行は常軌を逸して同じ政策を繰り返すということだ。しかし皆さんは国家的経済問題の解法を一つだけ示されたとすると、これは今の状況で言うと当局が通貨を監督管理しているということだが、皆さんはたぶん他のどのような手法よりもその政策の有効性を最終的に信じることになろう。

That is the position in which Jay Powell, the Fed’s chairman finds himself. Quite reasonably, he took the view that the Fed’s marriage with the markets was bound to go through another rough patch, and the Fed should use the good times to prepare itself. Unfortunately, the rough patch materialised before he could organise the Fed’s balance sheet for its next launch of monetary bazookas.

The whole monetary planning process has had to go on hold, and a mini-salvation of the economy engineered. To be fair, this time it is Washington’s tariff fight with China and its alienation of the EU through trade protectionism that has interrupted the Fed’s plans rather than the Fed’s mistakes alone. But by taking early action the hope is the Fed can keep confidence bubbling along for another year or two. It might work, but it will need a far more constructive approach towards global trade from America’s political-security complex to have a sporting chance of succeeding.

それはJay Powellの立場だ、FED議長自らがその立場を明らかにすることだ。これは全く合理的だ、彼はFEDの市場との結婚の将来を見通し、難しい問題に直面している、そしてFEDはそれに備える時だ。残念なことに、彼がFED議長として次に金融バズーカとしてFEDバランスシートを整える前に問題が顕在化した。金融計画全体が保留となり、小規模な経済救済と成らざるを得なかった。公平に見て、今回はFEDの誤政策というわけではなく、ワシントン政府が中国と関税戦争を始め、欧州と保護貿易で対立した、これがFEDの計画を中断させた。しかし対応が素早かったために、FEDはまだ今後数年はバブルを維持してくれるだろうという期待が残った。これがうまくゆくかもしれない、しかし米国の安全保障を考える上で、世界貿易政策としてはもっと建設的なものが必要だろう。

However, buying off a crisis by more money-printing does not represent a solution. It is commonly agreed that the problem screaming at us is too much debt. Yet, the inflationists fail to connect growing debt with monetary expansion. The Fed’s objective is to encourage the commercial banks to keep expanding credit. What else is this other than creating more debt?

しかしながら、危機を回避するために、さらに紙幣印刷をするというのは解決策ではない。だれもが認めることだが、あまりに大きな債務を抱えている。ただ、通貨膨張論者は債務増加と金融緩和を関連付けない。FEDの目的は商業銀行の貸出拡大だ。いったいこれ以上に債務を増やす方法があるだろうか?

Powell is surely aware of this and must feel trapped. However, what his feelings are is immaterial; his contractual obligation is to keep the show on the road, targeting self-serving definitions of employment and price inflation. He will be keeping his fingers crossed that some miracle will turn up.

Powellはたしかにこのことに気づいており罠に落ちいているに違いない。しかしながら、彼がどう感じるかはどうでも良い:彼の責務は以下のことを実行することだ、自ら定めた雇用と物価目標を守ることだ。彼はなにか奇跡でも起きないかと願っているに違いない。

FEDが金融不均衡の崩壊を後伸ばしする動きにでるかどうか判断するのにはまだ早すぎる、この崩壊点を迎えると貸しても借りてもチャラになる。この記事の目的はそういうことを解説するものではない、その議論の背景にある仮定がまったく間違っているかを指摘することだ、金利とはお金のコストであり、これが有益な結果を生み出すように管理されるべきだ、しかしこれが全くそうなっていない。もし資金需要や債務が金利で管理されるなら、公式金利と、貨幣量や与信総量、との間には負の相関が在るはずだ。下のチャートを見れば明らかだがこの関係が成り立っていない。

This chart covers the most violent moves in Fed-directed interest rates ever, following the 1970s price inflation crisis. Despite the Fed increasing the FFR from 4.6% in January 1977 to 19.3% in April 1980, M3 (broad money and bank credit) continued to increase with little variation in its pace. Falls in the FFR designed to stimulate the economy and prevent recession were equally ineffective as M3 continued on its straight-line path after 1980 without significant variation, and it is still doing so today. There is no correlation between changes in interest rates, the quantity of money, and therefore the inflationary consequences.

このチャートが示すのは、FEDが管理する金利が最も大きく動いた時期のものだ、1970年代の物価インフレ危機の後を示す。FEDはFFRを1977年1月の4.6%から1980年4月の19.3%まで増やしたが、M3(広義マネーと銀行貸出)は増加を続けた、その増加速度にはほとんど変化がなかった。景気刺激と景気後退回避でFFRを下げたが効果はなかった、M3は1980年以降も大きね変化はなく増加を続けた、そして現在も増え続けている。これを見て解るように金利変化と貨幣量の間に相関は無い、そしてインフレが起きている。

Gibson’s paradox disproves the efficacy of monetary policy

ギブソンの逆説は金融政策の有効性に疑問を呈する。

上のチャートで示すように、金融政策の主要課題は明らかだ、「金利で通過量を制御できる、」なんてことは受け入れることができないのは結果を見れば明らかだ、そして一般に思われているように「金利の役割は、一般に信じられているように与信需要を調整できる」なんてわけでもない。これはGibsonの逆説で確認されている、長期的には借金金利と卸売物価の間には正の相関があるが、近代経済を見るとこれとは全く逆の事が起きている。この状況を示すのが第二のチャートだ、2世紀に渡る英国の統計を示している。

Economists dismissed the contradiction of Gibson’s paradox because it conflicted with their set view, that interest rates regulate demand for money and therefore prices[i]. Instead, it is ignored, but the evidence is clear. Historically, interest rates have tracked the general price level, not the annual inflation rate. As a means of managing monetary policy, interest rates and therefore borrowing costs are ineffective, as confirmed in our third chart below.

エコノミストはギブソンのパラドックスの矛盾を無視する、その理由は既存概念からすると混乱するからだ、というのも「金利は資金需要を調整しその結果物価も調整する」と多くの人は理解している。無視されるにもかかわらず、証拠は明らかだ。歴史的にみると、金利は物価レベルを追いかける、インフレ率ではない。金融政策の一環として、金利や借金コストは無効だ、これは3枚目のチャートを見れば解ることだ。

The only apparent correlation between borrowing costs and price inflation occurred in the 1970s, when price inflation took off, and bond and money markets woke up to the collapsing purchasing power of the currency.

資金調達コスト(金利)とインフレ率のあいだに明らかな相関があったのは1970年代だけだ、この時物価インフレ率が上昇し始めた、そして債権と短期金利市場が目覚めて通貨の購買力が崩壊した。

The explanation for Gibson’s paradox, which embarrassingly eluded all the great economists who tackled it, is simple. It stands to reason that if the general price level changes, in aggregate businessmen in their calculations will take that into account when it comes to assessing the level of interest they are prepared to pay and still make a profit. If a businessman expects higher prices in the market, he will expect a higher rate of return and therefore be prepared to pay a higher rate of interest. And if prices are lower, he can only afford to pay a correspondingly lower rate. This holds true when capital in the form of savings is limited by the preparedness of people to save, and businesses have to compete for it.

ギブソンのパラドックスの解説、多くの著名なエコノミストが挑戦したがみなこれに言及することを避けた、この解説はとてもシンプルなものだ。こういうビジネスマンの行動は理にかなうものだ、もし物価がレベルが変わったら、利に聡いビジネスマンたちは金利が高くても利益を出せると推測するだろう。もしビジネスマンが市場での物価上昇を予想するなら、儲けも増えると期待し金利が高くても納得するだろう。もし物価が下がると、彼らは低金利しか許さないだろう。貯蓄をしようとする人の資金に限定するならこれも正しいことだ、そしてビジネスもこれとの競合せざるを得ない。

Today, Gibson’s paradox does not appear to apply, partly because capital is no longer scarce (thanks due to central banks) and partly because the abandonment of the Bretton Woods agreement has led to indices of the general price level rising continually. To these factors must now be added wilful misrepresentation of price inflation in official statistics, a deceit that will almost certainly end up destabilising attempts at economic management even further when discovered.

現在ではギブソンのパラドックスは適用されるわけではない、その一因は資金は潤沢にある(これは中央銀行のおかげだ)そしてもう一因はBretton Woods合意の放棄で物価は常に上昇し続けているためだ。これらの要因に加えて、今では公式統計の物価インフレ率は故意に捻じ曲げられている、このデタラメが経済運営を不安定にしている。

These points notwithstanding, the belief that interest rates are a price which regulates demand for money is disproved. The mistake is to ignore the human dimension of time preference and assume there is no reason for a difference in intertemporal values, the value of something today compared with later. To understand why the degradation of value over time becomes a necessary element of compensation in lending contracts, we must examine in more detail what interest rates actually represent. Only then can we fully understand why they do not correlate with changes in the general level of prices and the growth of credit, which makes up the bulk of M3 in the first chart.

こういう指摘にもかかわらず、金利が資金需要を調整するという間違った考えが信じられている。この誤解は人が time preference (現在価値と将来価値の違い)を無視していることから生まれる、そして時間に伴う価値の変化はないと仮定してしまっている、現在の価値と将来の価値とを較べる時だ。時間と共に価値はどうして劣化するかを理解すれば、貸付契約の対価が必要となることがわかる、これからもっと詳細に金利とは何かについてもっと知らなければならない。これを知ることで、我々は価格レベルの変化と与信増加の間にどうして相関が無いかを良く理解できるようになる、この与信が最初のチャートのM3で示したものだ。

The role of time preference

time preference 時間先取りの役割

どのような貸借契約においても、利息はいろいろな要因を反映している。リスク・プレミアム要因としては、借り手の信用、起業家リスク、そして貸出目的がある。その時々の誰もが認める金利がある、経済環境に応じたtime preference 時間先取りの金利によるものだ、これをオーストリア経済学派は originary rate という。Time preference 時間先取りというのは同じ満足度が得られるにしても、早く実現できるものと後ほど得られるものでは価値に違いがあるということだ。

Mainstream macroeconomists deny the existence of time preference, claiming that interest represents the rental of money. If that is all interest represents, then it can be reduced for the benefit of producers and consumers, and beyond savers losing out, no other consequences need occur. Furthermore, the denial of a subjective human element is always necessary for a mathematical approach to prices to be credible.

主流派マクロ経済学者はこの time preference 時間先取りの概念を否定する、そうではなく金利とはお金の貸出料金だという。これが金利の全てというなら、producers(貸し手)とconsumers(借り手)ともに恩恵は少なくなる、ましてや貯蓄は意味をなくする、他の意味合いが必要だ。更にいうと、人の存在を否定してしまうと、価格の裏付けは数学的な手法に頼ってしまう。

Despite it being unfashionable, we must briefly summarise pure time preference theory. Time preference is always present because time for any economic actor is finite and therefore has value. The more immediately that an action results in a satisfaction the more valuable that satisfaction compared with an action which leads to the satisfaction being delayed. It has been referred to by the old adage that a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.

それほど派手ではないが、我々は簡単に、純粋なtime preference theory を理解せねばならない。Time preferenceというのは常に存在する、というのもどの経済主体にとっても時間は有限で価値のあるものだからだ。もっと卑近に説明すると、同じ満足の得られる行為でも後からよりもいまえられた方がより価値がある。このことは昔からの格言でよく言われることだ、ヤブの中の二羽より手中の一羽。

The key to understanding the importance of time preference is to realise it is a human characteristic, and not something that emanates from the properties of individual goods and services. Intertemporal price differences can vary considerably between products, mainly due to their individual supply and demand characteristics. Because pure time preference is an underlying determinant of human action, the general rule is that the greater the difference in time between deciding on a course of action and the delivery of the satisfaction, the less the present value of that future action. From our individual experiences, we all know this to be true.

time preferenceの重要性を理解する鍵は人間の特質に気づくことだ、それは個々のモノやサービスから発せられるものではない。一時的な価格の変動は製品によってかなり変わる、主には需給関係に依存してだ。純粋な time preferenceは人間の行動が基準となるために、基本的なルールとして主に行動を起こす決断をした時と満足を得るときに大きな違いがある、将来の行動に対する現在価値は小さなものだ。我々の個人的な経験から、だれでもこのことをよく知っている。

Time preference is therefore the general intertemporal value placed on goods and services by consumers. It is not under the control of the producer, or for that matter a central bank. It is the consumer, the end-buyer of everything, that confirms the level of discount on future values, because consumers are humans acting with their human preferences.

Time preferenceとは消費者にとってもモノやサービスの一時的な価値とみなされる。生産者が制御する価値ではない、ましてや中央銀行でもない。それは消費者、最終的買い手となる、将来には価値が差し引かれる、というのも消費者は人間であり、人の好みに基づいて行動する。

In order to obtain monetary capital for any reason, the owners have to be persuaded to temporarily part with it for a compensation related to their general time preference. This is because they are being asked to defer their consumption, which is represented by the money borrowed. For convenience and by convention, compensation for the loss of the availability of money for immediate spending is expressed as an annualised interest rate. In this way, the variations of time preference for the full range of opinions and judgements of consumers over the whole gamut of goods and services finds expression in a basic, or originary rate of interest on money.

何らかの理由で金融資産を持とうとすると、その所有者は一時的な圧力を受ける、一般的な time preference に関する埋め合わせだ。だからこそ借金による消費は先延ばしできないかと自問する。伝統的に、直ちに支出するお金がない場合に、その埋め合わせを金利で表現する。こういうふうにして、全てのモノやサービスに対して消費者は異なるtime preference を持つ、これがお金に対する金利の始まりだ。

This fundamental human ranking of values matters to businessmen, because the longer it takes to produce a consumer good, the less the distant value of that good can be expected to be, expressed in today’s money. In assembling their capital resources, they take this time-related expense into account.

Therefore, in order to reduce the loss in value due to time preference, businessmen will always prefer the most efficient route available to final production. If, as is always the case today, a central bank commands through interest rate policy that the discount on future values is reduced, businessmen are no longer disciplined to prefer the most efficient route to production. The intertemporal discount is still there, but the suppression of originary interest rates by a central bank imposing a lower rate on the market creates an opportunity unrelated to the singular objective of providing consumer satisfaction.

この人間に備わる価値のランク付けがビジネスマンにとっては大切だ、というのも消費物を生産するのに時間がかかるほどに、そのものの予想価値が現在価値から乖離する。資金調達するときに、彼らはこの time preference による損失を考慮する。ビジネスマンは常に最終製品を最も効率的に生み出す方策を望むだろう。現代ではありふれたことだが、もし中央銀行が金利英作で将来価値を下げるなら、ビジネスマンはもはや規律をもって効率的な生産をしなくなる。時間に関する割引がそこにはある、しかし中央銀行が低金利で本来の金利を抑圧するなら、消費者の満足とは無関係な好機を生み出す。

This is why suppressing interest rates leads to malinvestments, exposed when interest rates subsequently rise. This is what the current hiatus in the stalling US economy is really about.

これがどうして金利抑圧が malinvstments 不当な投資(訳注:たとえばテスラとかソフトバンク、太陽光発電のようなビジネス)を引き起こすかという理由だ、その後金利が上昇するとこれが明白になる。これが米国経済が現在の停滞に陥っている理由だ。

It is clear, irrespective of monetary policy, that the originary interest rate is set by individuals in their roles as economic actors. That is not to say that in their decisions they are uninfluenced by official interest rates, but there is a tight limit to that influence. Instead, individuals will seize the opportunities presented by the difference between their own originary rate of interest and that set by the monetary authorities. An obvious example is residential property, where supressed interest rates persuade individuals to borrow cheap mortgage money to buy houses, purely because the interest payable is less than that suggested by personal time preferences. The same is true of financing the purchases of purely financial assets, and it is also a key reason behind the expansion of consumer credit.

金融政策とは無関係に、源金利は経済要因により個別に定められることは明らかだ。だからといってビジネスマンが公式金利の影響を受けないわけではない、そうではなく影響には限界がある。むしろ、自らの源金利と金融政策によって定めらた金利の違いによって、個々人は機会を捉えるだろう。明らかな例は住宅不動産だ、この分野では住宅購入のための借金を促進するために金利が抑えられている、なぜならば純粋に支払い可能な金利が個人的な time preference より小さくなるようにしている。同様のことが金融資産購入の際の融資にも当てはまる、そしてこれはまた消費者金融が拡大する重要な原因だ。

The suppression of interest rates to levels below those collectively determined by consumers in their time preferences is the fundamental source of inflations, booms, bubbles, and subsequent busts.

消費者が自然に持つ time preference よりも低い金利に抑え込むことで、インフレ、ブーム、バブルその後のバブル破壊を引き起こす基礎を形成する。

Essentially, a central bank’s interest rate policies distort markets, but they cannot significantly change that originary rate of interest. That is in the lap of time preference, set semi-consciously by consumers. The relationships between lenders and borrowers of monetary capital are further distorted by tax, because today’s governments commonly regard interest income as quasi-usurious and therefore a target for reducing the implied inequality of some individuals possessing significant levels of savings compared with others.

基本的なことは、中央銀行の金利政策は市場を歪める、しかし彼らも本来の金利を大きく変えることはできない。本来の金利というのは time preference から生じるものであり、消費者の判断によるものだ。金融資本に関して貸し手と借りての関係は税金で大きく歪んでいる、というのも今日の政府の立場は金利というのは高いもので、貯蓄の多い人とそうでない人の格差を緩和するために利息は課税対象となる。

Taxation on interest interferes with time preference, which was demonstrated through its absence on savings in the two most successful post-war economies, those of Japan and Germany. In Japan, tax-free post office savings accounts grew as a means of earning interest without being taxed, and in Germany the Federal Central Tax Office didn’t much bother collecting the withholding tax on bond interest at least until the 1980s, because to do so simply chased money out of Germany into savings accounts in Luxembourg and Switzerland beyond the reach of the tax office. Consumers in both Japan and Germany still retain a general savings habit that contributes to a relatively stable level of time preference, characteristics which have been central to their economic success.

利息に課税するとこで time preference に介入し、第二次世界大戦後の最も成功した2経済圏において貯蓄において time preferenceが無くなってしまった、日本とドイツだ。日本においては、郵便貯金の利息を非課税にしたので、この口座が増えた、そしてドイツではFederal Central Tax Officeは1980年台まで国債金利に課税しなかった、このために預金口座がドイツからルクセンブルグやスイスに逃げ出した、税金回避のためだ。日独共に消費者の貯蓄習慣は保たれ安定した time preferenceを保った、これが経済的成功の源となった。

The examples of Germany and Japan contrast with other socialised economies where savings have been discouraged through tax discrimination. The replacement of savings in the US and UK by bank credit and central bank base money has been a sad failure in comparison.

日独の例は社会主義経済とは際立つものだ、社会主義国では税金のために貯蓄の意欲が削がれた。米国や英国では銀行からの借金が貯蓄の代替となり、中央銀行のベースマネーが悲しい結末を迎えた。

So far, we have only addressed time preference on the assumption there is no change in money’s purchasing power. If, as is always true today, money’s purchasing power is continually declining, then to the extent the general public is aware of it, that widens the gulf between official interest rates and time preference even further. And if savers realise the true extent that the currency of their savings is losing purchasing power instead of believing self-serving government statistics, they could be forgiven for discounting future satisfactions even more heavily.

今までのところ、time preferenceに関してマネーの購買力に変化はないと仮定してきた。現在ではあたりまえのことだが、もしマネーの購買力が下落を続けるなら、一般大衆もこのことに気づく、こうなると公式な金利と time preference の間の溝が広がる一方だ。そしてもし預金者たちが、自ら貯蓄した通貨が政府統計と違い購買力を失っていることに気づくと、将来の満足が大きく割引されているのも無理はない。

This explains why, when the authorities respond to rising price inflation by raising interest rates, all they are doing is belatedly attempting to narrow an already widening gap between their version of where interest rates should be and the market’s rising originary rate. The expansion of bank credit does not slow, because the gap is still there and increasing as well.

この状況が、どうして、どういうときに当局が金利引き上げで物価上昇に対処するかを説明してくれる、彼らはギャップを狭めようとしている、本来の金利がどこにあるべきか、ということと市場が本来の金利を押し上げていることとのギャップだ。銀行与信の拡大は鈍化することはない、というのもこのギャップはまだ存在し広がり続けているからだ。

We saw this demonstrated in the 1970s, when rising interest rates failed to slow demand for credit, which continued to rise regardless. The rate of price inflation was also rising, persuading borrowers that the purchasing power of money was falling at an accelerating rate, thereby increasing their time preferences faster than compensated for by official interest rates.

我々はこの状況を1970年代にも目の当たりにした、金利上昇局面で与信需要は鈍化しなかった、なにがあろうと与信需要は増え続けた。同時に物価上昇も進行した、借り手を説得するのはこういう論法だ、金利上昇が加速するほどにマネーの購買力は下落する、しかるに、本来状況を補償するはずの公式金利よりも time preference増加の方が早い、という論法だ。

That ended in the early 1980s, when expectations of escalating prices were finally broken by 20%+ prime rates. In the 1980s demand for credit continued to increase, despite falling interest rates, because of financial and banking liberalisation which more than offset the failures associated with malinvestments. Broad money continued to grow with minimal variation as if nothing had happened, as it still does today.

これが終了したのは1980年代はじめのことだ、プライムレートが20%を超えて物価上昇が収まった。1980年代になると与信需要は引き続き増加した、金利下落にもかかわらずだ、というのも金融銀行自由化が進みmalinvestmentによる破綻を相殺したのだ。Broad moneyは躊躇なく増加を続けた、まるで何事もなかったように、これが現在も続いている。

The European Central Bank should pay attention to its failures as well. Its introduction of negative deposit rates, in defiance of all-time preference, has failed to stimulate production and consumption beyond government spending. Admittedly, negative rates have not generally been passed on to businesses and borrowing consumers, often for structural reasons. Instead, the ECB’s negative interest rates have benefited profligate Eurozone governments, allowing them to tax savers deposits instead of paying for time preference. It should be clear that negative interest rates cannot be justified so long as humanity values a satisfaction today more than the same satisfaction at a future date.

ECBでの失敗も注目すべきだ。彼らはマイナス金利を導入した、前代未聞の挑戦にもかかわらず、生産や消費を刺激することができなかった、政府歳出が増えただけだ。たしかに、マイナス金利はビジネスや個人債務には適用されなかった、多くは構造的な理由からだ。しかしながら、ECBのマイナス金利は放蕩を続ける欧州政府にとっては恩恵のあるものだった、そういう国では預金に課税することを可能にし、 time preference を免れた。ここで明らかにすべきだが、マイナス金利は人間の価値観から正当化されるものではない、何らかの行為で現在得られる満足が将来の満足よりも価値があると感じる人間の感性だ。

The implications for today’s economy

現在の経済への適応

金融政策が金融インフレを生み出すことに失敗した一方で、金利抑制により経済危機の種がまかれた。多くの人の持つ time preferenceにより生み出される本源的金利よりも実金利を抑制することはいつもmalinvestments(すぐに思い当たるのが、テスラやソフトバンク、太陽光発電等)を引き起こし、その後の金利上昇局面では常にこれらの malinvestmentは無防備になる。ビジネス面での対応はいつも同じことだ:malinvestments は先送りになるか取りやめとなるかだ。

Banks sense the mood-change in their customers and the associated increase in lending risk. They restrict their credit lines and working capital facilities to those they deem vulnerable, usually the medium and smaller enterprises that make up Pareto’s 80% of the economy[ii]. The economy then runs into a brick wall with a rapidity that surprises everyone. Labour shortages disappear, followed by employees being laid off. An unstoppable process of correcting earlier malinvestments gathers pace.

銀行は顧客の mood-change やそれに伴う貸出リスク増加を感じ取る。彼らは与信限度を引き締め、脆弱とみなされる企業への投資資金の適正化を計る、一般的には中小企業に対するもので、パレートの法則で経済の80%を占める部分だ。経済は急速に手詰まりになり誰もを驚かす。労働力不足は消え去り、労働者は解雇される。初期の malinvestment はとどまるところを知らず調整される。

This is the point in the credit cycle at which we appear to have arrived today. If only central bankers had taken the long-run evidence of their own statistics seriously, if they had only paid attention to the message from Gibson’s paradox, and if they had noted the madness of doing the same thing time after time despite it not working, we would have been blessed with a far greater degree of economic stability, instead of the increasing certainty of another financial and systemic crisis.

ここで述べたことが現在我々が到達している与信サイクルだ。もし中央銀行が自らの長年の行動とその結末を真剣に評価する場合に限り、そして彼らがギブソンのパラドックスの意味するところに注意を払うならば、さらには彼らが何度も何度も約にも絶たない同じことをしてきたことに気づくなら、我々は経済安定が高まる福音を受けることだろう、むしろ今は次の金融システム危機が来ることがどんどん確からしくなっている。

As for the hope that cutting interest rates will somehow lead to an expansion of bank credit, don’t hold your breath. The other lesson we should all learn is money supply continues to increase, if not in the form of bank credit then in the form of central bank base money. This is because the alternative of widespread bankruptcies is always unpalatable to a socialising state.

金利を切り下げることでなんとかして銀行与信拡大を望むが、あまり期待しないことだ。他の教訓としてはマネーサプライは増加を続けていることを学ぶことだ、銀行の与信供与ではなく、中央銀行のベースマネーの形で増えている。だからこそ、よく知られた破綻以外に、社会主義国ではいつも受け入れがたい(社会主義はやがて破綻する)。